Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 2025, No. 15, 1- 30.

Edited by Cátedra de Comunicación y Salud

ISSN: 2173-1675

Received 03/06/2024

Accepted 03/10/2024

Published 25/02/2025

CITIZEN SCIENCE AND SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION: WHAT, WHEN, WHERE AND HOW TO INFORM AND WHO SHOULD COMMUNICATE ABOUT LONG COVID

Jennifer García Carrizo[1]: Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

jennnifergarciacarrizo@gmail.com

Manuel Gertrudix: Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

Funding. This work was supported by the Autonomous Community of Madrid and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund-FEDER) [project number LONG-COVID-EXP-CM]. JGC is supported by a Juan de la Cierva-Formación fellowship (FJC2020-044083-I) funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

How to cite this article:

García Carrizo, Jennifer & Gertrudix, Manuel (2025). Citizen Science and Scientific Communication: What, When, Where and How to inform and Who should communicate about Long COVID. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 15, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2025.15.e364

Abstract

Introduction: The lack of adequate health information, especially during crises such as COVID-19, creates distrust and misinformation, which negatively impacts public health and medical care. Long COVID patients face scepticism, highlighting the urgency of improved communication and research to support their recovery. Methodology: Structured interviews with 42 Long COVID patients, 10 healthcare professionals, and 11 health communication specialists to obtain a comprehensive picture of the situation and develop recommendations. Results: The need for institutional recognition of Long COVID is emphasized. The creation of official digital platforms and increased awareness among primary care physicians is suggested. The importance of collaboration between government bodies, associations, patient groups, and communication experts is emphasised to provide multidisciplinary and transparent information, considering the evolution of scientific research. Discussion: Improving the communication and recognition of Long COVID can reduce misinformation and distrust. Collaboration between actors is key to ensuring effective and accurate information dissemination. Scientific communication actions, such as conferences and reports, are significant steps to raise awareness among society and health professionals about Long COVID. Conclusions: It is crucial to optimize the dissemination of information about Long COVID via official digital platforms and increase medical awareness. Multidisciplinary collaboration and scientific communication activities are essential to support patients and improve public health.

Keywords:

Long COVID, Scientific Communication, Citizen Science, information, recommendations.

1. INTRODUCTION

The lack of information has disastrous consequences for public health systems and society in general, at a local, national, and international level (Chou et al., 2018; Oyeyemi et al., 2014, Allgaier & Svalastog, 2015; Pathak et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2017; Larson, 2018; Nsoesie & Oladeji, 2020). The cost of the lack of information economically affects the healthcare system, which is overloaded with patients who have lots of questions and are seeking answers, journeying from one specialist to the next (Rodgers & Massac, 2020).

The lack of health information may create the impression that there is no consensus on an issue or that official sources of information are not credible (Chou et al., 2020), which induces feelings of anger, apathy, confusion, and mistrust (Sylvia Chou et al., 2020; Liu & Kim, 2011; Gibson-Helm et al., 2017). This can cause patients to stop searching for health information, avoid medical attention, or take self-managed health decisions that end up damaging their own health and collective health (Liu & Kim, 2011; Gibson-Helm et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2022).

During the COVID-19 health crisis, the lack of information has given rise to a genuine infodemic (World Health Organization, 2020), in which malinformation (Santos-d'Amorim & de Oliveira Miranda, 2021), misinformation, and disinformation (European Commission, 2020) have caused information chaos to the detriment of public health (Rocha et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated exponentially “the spread of misinformation” (Mian & Khan, 2020), which has required European Union authorities and member states to launch campaigns to counteract it, as is the case of the COVID-19 Disinformation Monitoring Programme (European Commission, 2022). Please note that “misinformation is false or inaccurate information that is deliberately created and is intentionally or unintentionally propagated. […] Disinformation also refers to inaccurate information which is usually distinguished from misinformation by the intention of deception” (Wu et al., 2019, p .80). Regarding Long COVID, although the information landscape displays these features this research focuses on the perspective of the lack of information.

Long COVID “refers collectively to the constellation of long-term symptoms that some people experience after they have had COVID-19” (World Health Organization, 2021). According to the World Health Organization “current evidence suggests approximately 10%-20% of people experience a variety of mid- and long-term effects after they recover from their initial illness” (World Health Organization, 2021). Other studies suggest that up to one in three adults may experience prolonged COVID symptoms lasting months after the initial infection, which causes distress and significant disability in those suffering from it (Laestadius et al., 2022).

However, despite institutional and research recognition of Long COVID, patients experiencing it are still met with scepticism and confusion from doctors on their symptoms that, according to the World Health Organization, include fatigue, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, memory, concentration or sleep problems, persistent cough, chest pain, trouble speaking, muscle aches, loss of smell or taste, depression or anxiety and fever (Rubin, 2020; Alwan, 2021; Yong, 2021; Rushforth et al., 2021). This is compounded by limited understanding from family members, friends, employers, and wider society, which hampers recovery both physically and psychologically (Laestadius et al., 2022).

To date, three main studies have been identified on communication, awareness-raising, and the supply of information linked to Long COVID (Laestadius et al., 2022, Miyake & Martin, 2021; Macpherson et al., 2022). They draw the same unanimous conclusion: the information given by official sources and the information provided by those affected is inconsistent and, consequently, “there is a need for greater understanding and communication about Long COVID at a number of levels (public, policy and healthcare professional)” (Macpherson et al., 2022, p.8).

2. OBJECTIVES

Further qualitative studies with patients, media and healthcare professionals are needed to better understand the lack of information associated with Long COVID. The main aim of this study is to compile a series of recommendations that facilitate the production of accurate, specific, and relevant information on Long COVID by official bodies from a citizen science perspective. This seeks to put an end to the existing lack of information on this condition, which would be useful for those affected in Spain and similar contexts.

In addition, in this discussion paper, we would like to briefly present various activities in the field of scientific communication, including participation in the organisation of the I National Congress on Long COVID: The Long COVID Experience, participation as invited speakers at the XVII Congress of the National Association of Health Informers and as speakers at the III Congress of the National Association of Health Informers. This also includes participation in reports on Long COVID and the way it should be communicated on Canarian television and in the EFE agency, as well as the development of a guide to improve the informative treatment of persistent COVID. All these actions were undertaken to actively involve the people and groups concerned in the research topic and the dissemination of the results, always from a citizen science perspective.

3. METHODOLOGY

This study uses a descriptive method that entails discourse analysis. It is based on structured interviews following Lasswell’s Five W’s model of communication and was developed on a sample of three target audiences: people affected by Long COVID, healthcare workers, and specialists in healthcare communication. This research intends to triangulate the needs and desires of affected people; what are media and health communication specialists doing in their routine work and what do healthcare workers think is the best.

The choice of Laswell's model corresponds to its simplicity in dissecting and analysing each component of the communication process. This facilitates both the identification of discrepancies between patients' needs and health professionals' practises and the recognition of the strengths and weaknesses of the strategy used. This is particularly valuable in contexts with long-lasting crises and with complex effects, as is the case with the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, its application in communication and health studies remains valid in studies dealing with similar study objects, such as understanding the impact of communicative messages and ensuring that the recommendations received enable effective and understandable information to be offered (Nimako et al, 2023) or analysing disinformation and misinformation propagation models (Wei et al., 2022). Some of the known limitations of the model, such as its linear nature or the lack of feedback, do not pose a problem for our research, as the focus is on the structured and comparative analysis of the perceptions of different audiences rather than the dynamic interaction between them.

3.1. Participants

Interviews have been conducted on three types of profiles: a) people affected by Long COVID, b) specialists in healthcare communication in the Spanish media (primarily, journalists specializing in health communication or healthcare professionals with expertise in communication: 7 national digital newspaper employees, 2 hospital press representatives, and 2 journalists working in specialized health-focused digital media); and c) representatives of the national healthcare sector in Spain (2 researchers specialized in Long COVID, 4 registered nurses and 4 doctors of medicine) (for sex details, see Table 1). Note that, in the case of those affected by Long COVID, a significantly higher percentage of women than men have been interviewed despite the sample being chosen at random from those who volunteered to take part in this study. This difference is consistent with the fact that the symptoms of Long COVID are more prevalent in women (Nabavi, 2020; Asadi-Pooya, 2021; Bucciarelli et al., 2022; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas et al., 2022; Pelà et al., 2022; Raveendran et al., 2021) aged 35 to 69 (Torjesen, 2021; Office for National Statistics, 2022). In the participant’s informed consent, anonymity is guaranteed to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation and the Spanish Data Protection Act and to avoid re-identification of subjects through cross-data processing.

Table 1. Distribution by sex of the interviewees.

|

Profile |

Male |

Female |

|

People affected by Long COVID |

11 (26.20%) |

31 (73.80%) |

|

Spanish media representatives |

9 (82%) |

2 (8%) |

|

Representatives of the national healthcare sector in Spain |

6 (60%) |

4 (40%) |

Source: Own elaboration.

3.2. Recruitment

The participants of these interviews were recruited in different ways based on their profiles. People affected by Long COVID were recruited through Long COVID associations and networks that operate in Spain (see Appendix B). These associations were contacted by email and via their Twitter profile, the aims of the study were explained to them, and they were asked to distribute a Google Forms document amongst their members for those who were interested to register. This form collected the contact telephone of the affected people. The telephone numbers were randomised, and interviews were conducted until data saturation occurred.

In the case of the specialists in healthcare communication in the Spanish media, a database was compiled of the most representative media that operate specialised health sections. For healthcare workers, search and selection were conducted for specialists in the treatment of COVID and/or Long COVID in Spain. In both cases, they were contacted by email and interviews were conducted with those who accepted and responded to the initial contact.

None of the interviewees had any prior relationship with the interviewer and no participants refused to participate in the interview or left it.

3.3. Setting

The interviews of people affected by Long COVID were conducted by telephone between May and June 2022. The interviews of specialists in healthcare communication and healthcare specialists were conducted by videocall on Microsoft Teams between June and July 2022. In May 2024, a new series of interviews was conducted to check whether the results obtained in the first wave were still valid. To this end, interviews were conducted with a representative of a specialised health medium, a representative of health professionals and a representative of people affected by Long COVID, using the same procedure and protocol as described in this section.

3.4. Data collection

The interviews were conducted by Jennifer García Carrizo, hereinafter JGC, a postdoctoral researcher who has 9 years of experience in social sciences.

A total of 42 interviews were conducted with people affected by Long COVID. First, 30 interviews were conducted with people affected by Long COVID and, subsequently, interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation occurred. The interviews lasted from 5 to 18 minutes, with a mean length of nine minutes. The interviews followed a pre-prepared structured interview guide. The mean age of the patients interviewed was 48.9 years old.

Parallelly, 11 interviews were conducted with specialists in healthcare communication in Spanish media and 10 professionals from the healthcare sector who work in Spanish centres and hospitals. The number of interviews was also determined by theoretical saturation. The interviews of representatives of the media lasted from 11 to 34 minutes, with a mean length of 14 minutes. The interviews of representatives of the healthcare sector lasted from 12 to 44 minutes, with a mean length of 26 minutes.

All the interviews followed a structured interview guide based on Lasswell’s Five W’s model of communication: “Who Says What in Which Channel to Whom with What Effect” (Lasswell, 1948, p. 216). These inquiries pertain to the fundamental facets of the communication process. The first set of questions concerns the communicators themselves (Who) and the content of their message (What). The second focuses on the medium through which the message is transmitted from the sender to the receiver (Which Channel). The third question regards the receiver (to Whom). Finally, the last aspect concerns the impact or result of the communication, such as whether the audience was convinced to embrace the viewpoint conveyed in the message (With What Effect) (Lasswell, 1948, p. 216). Considering this formula as a starting point, the questionnaires were adapted to analyse five variables: 1. What to inform (What), 2. When to inform and 3. Where to inform (Which Channel), 4. Who should inform (Who), and 5. How to inform (Which Channel, to Whom and with What Effect). The goal is to describe the communicative actions that occur in the context of Long COVID from the perspective of the relevant actors.

Nevertheless, the questions were adapted to each interviewee's audience. Three different questionnaires were created based on whether the interviews were conducted on those affected by Long COVID, representatives of the media, or healthcare staff (see Appendix C). The interviews were recorded with the consent of the interviewees and, after the recordings were anonymised, they were transcribed using Sonix and were deleted to ensure data protection compliance.

3.5. Data analysis

JGC coded the data obtained from the interviews using an epistemological approach and a coding framework based on the Five W’s model of communication put forward by Lasswell (Office for National Statistics, 2022). Thematic analysis of the data was used to detect facilitators and barriers associated with the management of Long COVID-related information in Spanish society. After the initial coding framework was produced it was reviewed by both authors to remove and merge redundant code, as well as to create new code based on ideas that were not initially included in the first coding framework.

The data were analysed and coded in Atlas.ti. To simplify participation for the interviewees in this study and to not add to their workload, they were not required to review the data from the transcription of the interviews.

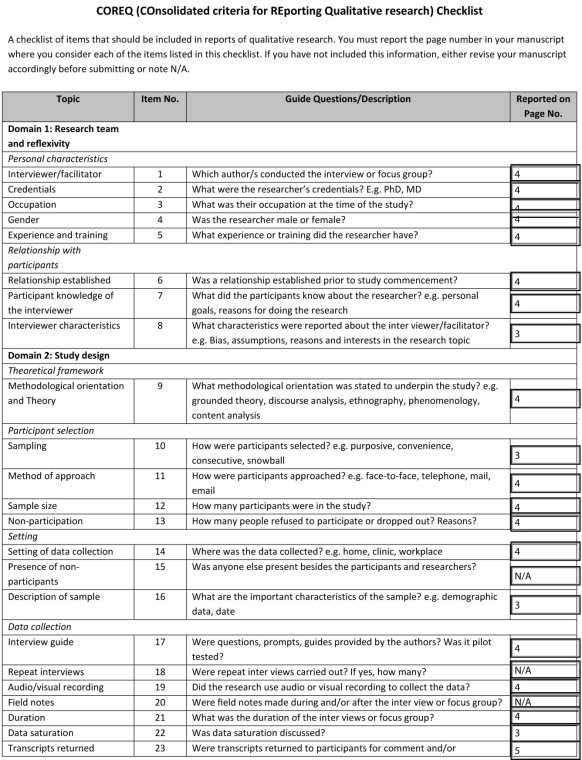

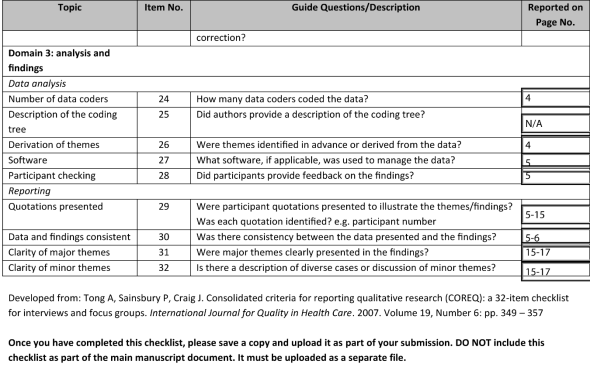

For further transparency, the reporting of this study follows the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007; see Appendix D). Besides, the results obtained are included in Appendix A of this paper and are publicly accesible as well in Zenodo (www.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7915905), organized by the categories established in the coding process and following Lasswell´s model.

4. RESULTS

Using Lasswell’s Five W’s model of communication (Lasswell, 1948), five study variables have been set (1. What to inform, 2. When to inform, 3. Where to inform, 4. Who should inform, and 5. How to inform) and the results have been classified into related subthemes in consideration of the points of view of the three interviewee profiles: patients, healthcare workers, and specialists in healthcare communication (see Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of the themes raised and relation to each variable under study.

|

Variable |

Themes and sub-themes |

|

1. What. What to inform |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Own elaboration.

4.1. What. What to inform

People affected by Long COVID report the need to have information on 1) the research that is being conducted on Long COVID, 2) workplace contact details for specialist Long COVID healthcare workers, 3) the symptoms and treatments to cure or ease the effects of Long COVID, 4) the existence of Long COVID as an illness and institutional and healthcare authority recognition of it, and 5) the social, emotional, and work consequences that Long COVID has on their lives (see Table 3 – Appendix A).

Healthcare sector representatives emphasise the importance of raising awareness of the condition linked with Long COVID and the associated set of problems it entails, using an emotional and not exclusively clinical approach.

Specialists in healthcare communication report they mainly provide information on two topics related to Long COVID: 1) the release of relevant new studies or scientific results, 2) the presence of misinformation on social media, so as to warn of it. Moreover, they state that rather than providing information about Long COVID, they provide information on COVID in general and that most of the information they receive on Long COVID comes from accounts from patient associations and/or healthcare workers and scientific societies.

4.2. When. When to inform

Patients stress the idea that they would like to search for information online and have it come up easily, although they have not reported an ideal time when they would like to be informed or homogenous patterns in their searches for information. Whilst some state they look for information when they feel their symptoms have improved, others state they do so when they worsen. The same is found with the time of day, some search in the morning, some in the afternoon, and others later at night.

Healthcare workers are not unanimous either on when to provide information. Some argue that is important to do so continuously to raise awareness in the population of the problem, but others hold that this strategy leads to saturation and that it is better to do so when new relevant scientific-clinical findings come out or on specific occasions such as Long COVID Day. It should be noted that healthcare sector representatives signalled the importance of the primary health care (PHC) that is provided in Health Centres as a key channel for referring people affected by Long COVID or those who may present relevant clinical conditions to Post-COVID Units at Hospitals in the Spanish National Health System.

Regarding specialists in healthcare communication, they follow three core criteria on when to publish information: 1) immediately when new studies offering interesting results appear; 2) when fake news or disinformation is identified; and 3) when they detect concern on the issue in society (see Table 4 – Appendix A).

4.3. Where. Where to inform

In terms of where to inform, people affected by Long COVID express three ideas almost unanimously: 1) their interest in getting information in primary care centres and specialist centres; 2) the need for a centralised institutional platform that contains existing information on Long COVID; and 3) the importance of using the media as a means of raising awareness of their condition, but not as a means of providing information to those affected. They state that they do not trust the media and that the lack of official information has led them to having to find their own information online, on scientific platforms (Google Scholar), social media, and patient associations (see Table 5 – Appendix A).

Healthcare workers agree that it is they who should provide the necessary information to patients and that the media is a means for raising awareness of the illness. They hold that using general and specialist media platforms is key to raising awareness of the condition and informing different segments of society but with caution. They acknowledge that the media creates a certain sense of alarm and that there is a lack of accurate, verified information on Long COVID.

Specialists in healthcare communication acknowledge that information on Long COVID is covered on the front page or in secondary sections based on how new and important it is. They also usually include it in the Science, Health, and/or Society sections and share it on social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Telegram, and YouTube. Furthermore, although they do recognise that in certain cases a sense of alarm has been created by the media on COVID, they hold that they try to work to improve the existing information and debunk misinformation using reference sources. They also recognise the need to raise awareness of Long COVID, although, in the absence of conclusive results, they prefer not to cover the topic. They argue that the general population has reached saturation point on COVID and that it is patient associations and networks who are pressing the most for Long COVID to be discussed.

4.4. Who. Who should inform

Although the people affected by Long COVID interviewed have reported that they turn to existing patient collectives and associations for information, as well as acquaintances, family members and/or healthcare worker friends, they underline that it should also be the health authorities, family doctors, and specialist doctors who give them information. This idea is also held by healthcare workers. In fact, the latter recognises the role and work of patient associations as basic interlocutors in easing the flow of information between healthcare workers and patients. Nevertheless, they point to the need for these organisations to be well coordinated and organised so that they can perform their duties properly. For instance, they highlight that in Spain many Long COVID associations are being formed and it is important that they work together.

Specialists in healthcare communication, in turn, state that they have four key reference sources: 1) universities, researchers, and scientific journals; 2) health associations, healthcare workers, and hospitals; 3) official Government sources; and 4) patient associations. They also stress that there are two profiles of journalists who write about Long COVID: they are usually either professional journalists specialised in health or healthcare workers who have specialised in journalism (see Table 6 – Appendix A).

4.5. How. How to inform

Both patients and representatives of the healthcare sector stress the need for a multidisciplinary approach which unifies all the information on Long COVID. For healthcare workers it is also critical to address honestly the current lack of knowledge on Long COVID. It must be conveyed to the public that medicine is a changing science and that, as more research is conducted, the information on pathology is broadened and improved. Similarly, they emphasise the need to communicate that “there are no miracle cures” and that time is a key resource in science.

Specialists in healthcare communication hold that, in the interests of improving the scant existing information and to be able to offer accurate and precise information that patients and wider society will consider reliable, citing sources and providing quality references to scientific research, prestigious doctors, and official institutions is critical (see Table 7 – Appendix A).

5. DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

5.1. Discussion

This research identifies a series of needs aimed at improving communication on Long COVID. The results contribute to a little studied area, for which, at present, there are only a handful of studies that address disinformation on Long COVID (Laestadius et al., 2022; Miyake & Martin, 2021; Macpherson et al., 2022). This study includes the views of patients, healthcare workers, and specialists in healthcare communication to compile a series of guidelines to improve the current information landscape on Long COVID concerning the five variables studied: What is it relevant to give information about, When to do so, Where (which channels, media, and resources), Who should do so, and How (what approach).

5.1.1. What. What to inform

On what information to give when discussing Long COVID, based on the opinions of those affected by Long COVID, healthcare worker representatives, and specialists in healthcare communication, the following topics should be considered:

1. The existence of Long COVID as an illness and institutional and healthcare authority recognition of it. This ratifies the results of previous studies which highlight the need for more research, information, medical recognition, and investigate the gaslighting[2] that patients face when they see uninformed family doctors (Miyake & Martin, 2021; Boix & Merino, 2022).

2. The research that is being conducted on Long COVID. The fact that research is being conducted on an illness shows that there is social support for said illness, that institutions and the scientific community are interested in it, and this is key to patient recovery. Indeed, previous studies on illnesses such as cancer suggest that “the evidence for the relationship between social support and cancer progression is sufficiently strong” (Usta, 2012, p. 3570).

3. The social, emotional, work, and financial consequences that Long COVID has on the lives of those affected, through the accounts of patients, healthcare workers, and/or scientific societies. As shown by previous studies, it is essential to highlight that health problems cause social problems. This is particularly true in the financial aspect (Másilková, 2017).

Although patients reiterate the need to make visible the contact details of Post-COVID units and Long COVID specialists, we do not recommend this as in Spain primary health care resources have a “filter” effect that prevents unnecessary referrals to specialists, as shown in previous research (Gérvas & Pérez Fernández, 2005; van den Brink-Muinen et al., 2003). Nevertheless, it is necessary to stress the importance of primary health care doctors being aware of the route to follow if a patient presents in their practice with symptoms like those presented by those affected by Long COVID. Specifically, it is important to raise the profile of Post-COVID Units amongst primary health care professionals so that they are able to effectively perform the task of determining whether a patient needs to be referred or not.

5.1.2. When. When to inform

Regarding when to inform, the results do not provide evidence for a preferred setting or time of day to do so. Neither do they make clear whether it is best to do so continuously or in specific settings, as opinions are divided. However, as other studies have shown, doctors are the most trusted source of information for patients (Williams et al., 2019; Zeal et al., 2021) and their role is essential in combating disinformation (Mian & Khan, 2020). In the case of Long COVID, the affected groups agree on the importance of finding information in health centres and that primary health care professionals should refer people with symptoms linked to Long COVID to Post-COVID Units at Hospitals in the National Health System. As analysed by previous studies (Benigeri & Pluye, 2003), existing medical information online is of mixed quality and patients usually have problems finding, understanding and using it. Thus, to prevent certain harm and risks tied to the consumption of unreliable information, as well as the excessive consumption of information, the best course is to turn to healthcare workers, which confirms European Union recommendations (European Commission, 2020; Mian & Khan, 2020).

5.1.3. Where. Where to inform

Concerning where to inform, in consideration of the results of this study, the following is recommended:

1. Give information in primary care health centres and specialist centres because, as shown by other studies, not only are these the spaces patients prefer, but they are also the most trusted (Williams et al, 2019; Zeal et al., 2021).

2. Create an institutional platform that unifies all existing information. As previous studies have demonstrated, “eHealth platforms help reduce costs and improve the general quality of healthcare” (Dang et al., 2022, p. 6604).

3. Use the media and social media as a means of raising awareness of Long COVID but not as a conduit for giving patients information. It is not clear that these two pathways ensure that information reaches the full spectrum of patients in the health system, as has been shown previously (McCarroll et al., 2014) and, additionally, concerns on information quality and authority decreased patients’ engagement with information provided by the media and social networks (Zhao & Zhang, 2017). The media acts as a regulator between the affected people and the healthcare workers.

5.1.4. Who. Who should inform

Concerning who should provide information on Long COVID, it is recommended that health associations and/or scientific societies, official government sources, patient associations, and/or specialist communications professionals deliver it. It is also important that patients know which sources are reliable reference sources and that they avoid turning to friends or acquaintances, as the lack of information proliferates partly because it is highly likely that people accept information and advice from friends, family members, and people they feel their community trusts, as already evidenced (Chou et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it is important to remember that support groups are key to patient care, so, although they should not constitute sources of information, they can be sources of support and listening (Boix & Merino, 2022).

5.1.5. How. How to inform

Concerning how information should be provided, based on the results of this study, the following is recommended:

1. A multidisciplinary and unified approach, a practice also put forward by other studies in the assertion that setting up coordinated clinical pathways in the health system with integrated primary health care and hospital care and the creation of hospital-based specialist COVID clinics is key (Boix & Merino, 2022). With this motivation, the "I Long COVID Madrid Conference" was held on April 5, 2024, in Madrid, organized by specialist doctors from the 12 de Octubre Hospital, María Ruiz-Ruigómez, Estíbaliz Arrieta, and Carlos Lumbreras. The aim was to establish a dialogue between different specialists dealing with this disease and people affected by Long COVID.

2. Honestly addressing what the existing (and often changing) information on Long COVID is, as well as conveying to the general population the importance that time holds in scientific research in finding reliable and stable results. The matter is that “allowing room for mistakes and changes in evidence over time is important for science, disagreement being at least a driver of future innovation” (Southwell et al., 2019, p. 3), an idea that it is essential to make the public aware of (Zarcadoolas et al., 2005).

Finally, we would like to highlight the significance of our findings and the importance of effective scientific communication. After obtaining the presented results, we undertook various scientific communication initiatives to disseminate these findings among the key stakeholders: healthcare professionals, communication specialists, and individuals affected by Long COVID. These actions were also aimed at raising societal awareness about this phenomenon.

Among the activities for communicating the obtained results, the following stand out:

- Participation in the organisation of the “I National Congress on Long COVID: The Long COVID Experience”, which took place on 23 September 2022 at the Alcorcón campus of the University of Rey Juan Carlos and was attended by more than 200 participants. The event was organised by the University Rey Juan Carlos (URJC), the Professional School of Physiotherapists of the Community of Madrid and the Spanish Association of Physiotherapists (AEF). Firstly, the topic of long COVID was explored from different angles, including the systemic manifestation, pulmonary sequelae and the family medicine approach. Later in the day, the role of the media in disseminating information about Long COVID was discussed, followed by debates on associations around this disease. The focus then turned to physiotherapy approaches, covering aspects such as the immune system, respiratory symptoms, heart problems and chronic pain. The day ended with a closing session that provided a space for sharing knowledge and experiences between professionals and those affected by Long COVID. In addition, throughout the day there was a showroom where participants could view data analysing communication about Long COVID in the media and social networks in an immersive 3D environment created by the members of the Ciberimaginario group and the XR LAB COM of the URJC (please, see www.longCOVID.eu/subproyecto-11-discurso-mediatico).

- Participation as an invited speaker at the “XVII Congress of the National Association of Health Informers” on October 21 and 22, 2022, where the results of the research presented here were shared by Jennifer García Carrizo. Her presentation is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=umIPTetgSMU

- Participation in the “III International Congress of Communication and Health (CICyS)” held at the Complutense University of Madrid on April 25 and 26, 2024, where these results were disseminated within the scientific community. The presentation given is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=JIjiXkrng78. Participation in articles about Long COVID and how it should be communicated on Canarian television, within the program “Atlántico Noticias”, and in an interview conducted by the EFE Agency, which has had over 25 impacts in 6 international media from the USA, Mexico, France, and Peru, as well as national (Antena 3) and local media (see www.bit.ly/3HBwLjf).

- Development of a “Guide to Improve the Informational Treatment of Persistent COVID” published on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7432212) with over 460 visits and 290 downloads.

5.2. Conclusion and limitations

These recommendations seek to facilitate appropriate ways to generate truthful, accurate and effective information about Long COVID. This study opens the door for new research looking at the opinions of patients, health professionals and health communication professionals. It is important to note that this is an exploratory and qualitative study conducted in the absence of previous research in this area, which emphasises the need for future quantitative research. The comparative analysis of the data from the first survey wave in 2022 with the review carried out in 2024 shows that despite some measures and efforts on our part to improve the information on Long COVID (see discussion), work still needs to be done on this issue.

It would also be interesting to repeat this study in other countries to carry out international comparative analyses, as this study has analysed the situation in Spain. While COVID is a global problem, the specific socio-cultural, political and economic conditions mean that patients are experiencing this global crisis at a local level, which requires an appropriate localised response (Miyake & Martin, 2021). Future lines of research could address the health literacy of respondents concerning Long COVID. While this aspect is initially outside the scope of this study, it is of great interest (Zarcadoolas et al., 2005).

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

Messaging from official health institutions recognising Long COVID will help restore patient confidence in the health system, something which has ebbed (Gorman & Scales, 2021), especially due to the insufficient support that those affected have encountered in the saturated and overwhelmed medical care system (Mian & Khan, 2020). Additionally, it will promote recognition and awareness-raising of this condition and, consequently, help reduce the existing lack of information in the public and some primary health care doctors when addressing the problem of Long COVID. This will, at least, make patients feel heard. Otherwise, the lack of this institutional messaging may contribute to the widespread and continuous stigmatisation and marginalisation of those affected (Gorman & Scales, 2021).

Creating an official space offering precise information on the steps to follow will simplify the process for healthcare workers and patients. Whilst creating a platform that brings together all existing information in the area is a complex task, it is not that onerous to add a section in official state health information sources stating what Long COVID is and what to do if there is any suspect of suffering it. It would be interesting if this website included specific information that told possibly affected people that, firstly, they must consult their family doctor to assess whether they need to be referred to the Post-COVID Units in the Public Hospitals of the National Health System. This will also help healthcare professionals in primary health care centres to be clear on the procedure and the requisite circumstances for referring their patients to the correct units and, therefore, improve patient care.

7. REFERENCES

Allgaier, J., & Svalastog, A. L. (2015). The communication aspects of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Western Africa–do we need to counter one, two, or many epidemics? Croatian medical journal, 56(5), e496. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2015.56.496

Alwan, N. A. (2021). The teachings of Long COVID. Communications Medicine, 1(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-021-00016-0

Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Akbari, A., Emami, A., Lotfi, M., Rostamihosseinkhani, M., Nemati, H., ... & Shahisavandi, M. (2021). Risk factors associated with long COVID syndrome: a retrospective study. Iranian journal of medical sciences, 46(6), e428. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijms.2021.92080.2326

Benigeri, M., & Pluye, P. (2003). Shortcomings of health information on the Internet. Health promotion international, 18(4), 381-386. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dag409

Boix, V., & Merino, E. (2022). Post-COVID syndrome. The never ending challenge. Medicina Clinica (English Ed.), 158(4), 178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2021.10.005

van den Brink-Muinen, A., Verhaak, P. F., Bensing, J. M., Bahrs, O., Deveugele, M., Gask, L., ... & Peltenburg, M. (2003). Communication in general practice: differences between European countries. Family Practice, 20(4), 478-485. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmg426

Brown, K., Yahyouche, A., Haroon, S., Camaradou, J., & Turner, G. (2022). Long COVID and self-management. Lancet (London, England), 399(10322), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02798-7

Bucciarelli, V., Nasi, M., Bianco, F., Seferovic, J., Ivkovic, V., Gallina, S., & Mattioli, A. V. (2022). Depression pandemic and cardiovascular risk in the COVID-19 era and long COVID syndrome: gender makes a difference. Trends in cardiovascular medicine, 32(1), 12-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2021.09.009

Chou, W. Y. S., Gaysynsky, A., & Cappella, J. N. (2020). Where we go from here: health misinformation on social media. American journal of public health, 110(S3), S273-S275. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305905

Chou, W. Y. S., Oh, A., & Klein, W. M. (2018). Addressing health-related misinformation on social media. Jama, 320(23), 2417-2418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16865

Dang, D., Pekkola, S., Pham, S., & Vartiainen, T. (2022). Platformization practices of health information systems: A case of national ehealth platforms. In Proceedings of the 55th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/80140

European Commission. (2020). Policies. Tackling online disinformation. https://www.digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/online-disinformation

European Commission. (2022). COVID-19 disinformation monitoring programme. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/COVID-19-disinformation-monitoring

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C., Martín-Guerrero, J. D., Pellicer-Valero, Ó. J., Navarro-Pardo, E., Gómez-Mayordomo, V., Cuadrado, M. L., ... & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2022). Female sex is a risk factor associated with long-term post-COVID related-symptoms but not with COVID-19 symptoms: the LONG-COVID-EXP-CM multicenter study. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(2), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020413

Gérvas, J., & Pérez Fernández, M. (2005). El fundamento científico de la función de filtro del médico general. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 8, 205-218. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2005000200013

Gibson-Helm, M., Teede, H., Dunaif, A., & Dokras, A. (2017). Delayed diagnosis and a lack of information associated with dissatisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102(2), 604-612. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2963

Gorman J. & Scales D. (2021). Long COVID Is Pitting Patients Against Doctors. That's a Problem. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/965494

Laestadius, L. I., Guidry, J. P., Bishop, A., & Campos-Castillo, C. (2022). State health department communication about long COVID in the United States on Facebook: risks, prevention, and support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5973. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105973

Larson, H.J. (2018). The biggest pandemic risk? Viral misinformation. NATURE, 562, 309-310. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07034-4

Lasswell, H.D. (1948). The structure and function of communication in society. The communication of ideas, 37(1), 136-139. https://www.sipa.jlu.edu.cn/__local/E/39/71/4CE63D3C04A10B5795F0108EBE6_A7BC17AA_34AAE.pdf

Liu, B. F., & Kim, S. (2011). How organizations framed the 2009 H1N1 pandemic via social and traditional media: Implications for US health communicators. Public relations review, 37(3), 233-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.03.005

Macpherson, K., Cooper, K., Harbour, J., Mahal, D., Miller, C., & Nairn, M. (2022). Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ open, 12(1), e050979. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050979

Másilková, M. (2017). Sociálně zdravotní důsledky dopravních nehod. KONTAKT, 19(1), e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kontakt.2017.01.007

McCarroll, M. L., Armbruster, S. D., Chung, J. E., Kim, J., McKenzie, A., & von Gruenigen, V. E. (2014). Health care and social media platforms in hospitals. Health communication, 29(9), 947-952. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.813831

Mian, A., & Khan, S. (2020). Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. BMC medicine, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01556-3

Miyake, E., & Martin, S. (2021). Long COVID: Online patient narratives, public health communication and vaccine hesitancy. Digital health, 7, e20552076211059649. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076211059649

Nabavi, N. (2020). Long COVID: How to define it and how to manage it. BMJ, 370, m3489 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3489

Nimako, B. A., Yao, L., & He, Q. (2023). Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: A rapid review. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 867. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09869-8

Nsoesie, E. O., & Oladeji, O. (2020). Identifying patterns to prevent the spread of misinformation during epidemics. The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-014

Office for National Statistics (2022). Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronavirusCOVID19infectionintheuk/7july2022

Oyeyemi, S. O., Gabarron, E., & Wynn, R. (2014). Ebola, Twitter, and misinformation: a dangerous combination? Bmj, 349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6178

Pathak, R., Poudel, D. R., Karmacharya, P., Pathak, A., Aryal, M. R., Mahmood, M., & Donato, A. A. (2015). YouTube as a source of information on Ebola virus disease. North American journal of medical sciences, 7(7), e306. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.161244

Pelà, G., Goldoni, M., Solinas, E., Cavalli, C., Tagliaferri, S., Ranzieri, S., ... & Chetta, A. (2022). Sex-related differences in long-COVID-19 syndrome. Journal of Women's Health, 31(5), 620-630. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0411

Raveendran, A. V., Jayadevan, R., & Sashidharan, S. (2021). Long COVID: an overview. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 15(3), 869-875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007

Roberts, H., Seymour, B., Fish, S. A., Robinson, E., & Zuckerman, E. (2017). Digital health communication and global public influence: a study of the Ebola epidemic. Journal of Health Communication, 22(sup1), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1209598

Rocha, Y. M., de Moura, G. A., Desidério, G. A., de Oliveira, C. H., Lourenço, F. D., & de Figueiredo Nicolete, L. D. (2021). The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01658-z

Rodgers, K., & Massac, N. (2020). Misinformation: a threat to the public's health and the public health system. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 26(3), 294-296. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001163

Rubin, R. (2020). As their numbers grow, COVID-19 “long haulers” stump experts. Jama, 324(14), 1381-1383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17709

Rushforth, A., Ladds, E., Wieringa, S., Taylor, S., Husain, L., & Greenhalgh, T. (2021). Long COVID–the illness narratives. Social science & medicine, 286, 114326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114326

Santos-d'Amorim, K., & de Oliveira Miranda, M. F. (2021). Informação incorreta, desinformação e má informação: Esclarecendo definições e exemplos em tempos de desinfodemia. Encontros Bibli: Revista eletrônica de Biblioteconomia e Ciência da informação, 26, 01-23. https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2021.e76900

Southwell, B. G., Niederdeppe, J., Cappella, J. N., Gaysynsky, A., Kelley, D. E., Oh, A., ... & Chou, W. Y. S. (2019). Misinformation as a misunderstood challenge to public health. American journal of preventive medicine, 57(2), 282-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.009

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care, 19(6), 349-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Torjesen, I. (2021). COVID-19: Middle aged women face greater risk of debilitating long-term symptoms. Brit Med J, 372(829). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n829

Usta, Y. Y. (2012). Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 13(8), 3569-3572. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3569

Wei, H., Chen, J., Gan, X., & Liang, Z. (2022). Eight-element communication model for Internet health rumors: A new exploration of Lasswell’s “5W Communication Model”. Healthcare, 10(12), 2507. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122507

Williams, S. L., Ames, K., & Lawson, C. (2019). Preferences and trust in traditional and non-traditional sources of health information–a study of middle to older aged Australian adults. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 12(2), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2019.1642050

World Health Organization (2020). Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Promoting healthy behaviours and mitigating the harm from misinformation and disinformation. Joint statement by WHO, UN, UNICEF, UNDP, UNESCO, UNAIDS, ITU, UN Global Pulse, and IFRC. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-COVID-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation

World Health Organization (2021). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 condition. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(COVID-19)-post-COVID-19-condition

Wu, L., Morstatter, F., Carley, K. M., & Liu, H. (2019). Misinformation in social media: definition, manipulation, and detection. ACM SIGKDD explorations newsletter, 21(2), 80-90. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373464.3373475

Yong, S. J. (2021). Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infectious diseases, 53(10), 737-754. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397

Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., & Greer, D. S. (2005). Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health promotion international, 20(2), 195-203. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dah609

Zeal, C., Paul, R., Dorsey, M., Politi, M. C., & Madden, T. (2021). Young women's preferences for contraceptive education: The importance of the clinician in three US health centers in 2017-2018. Contraception, 104(5), 553-555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.005

Zhao, Y., & Zhang, J. (2017). Consumer health information seeking in social media: a literature review. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 34(4), 268-283. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12192

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS, FINANCING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conceptualization: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Gertrudix, Manuel. Methodology: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Gertrudix, Manuel. Methodology: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Barrio, Manuel. Formal Analysis: García Carrizo, Jennifer. Data curation: García Carrizo, Jennifer. Writing-Preparation of the original draft: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Barrio, Manuel. Writing-Review and Editing: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Barrio, Manuel. Visualization: García Carrizo, Jennifer. Supervision: Barrio, Manuel. Project administration: Barrio, Manuel. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: García Carrizo, Jennifer and Barrio, Manuel.

Funding: This work was supported by the Autonomous Community of Madrid and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund-FEDER) [project number LONG-COVID-EXP-CM]. JGC is supported by a Juan de la Cierva-Formación fellowship (FJC2020-044083-I) funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the participants for their participation in the interviews.

Conflict of interest: This research was conducted in the absence of any potential conflict of interest.

AUTHORS

Jennifer García Carrizo

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Teacher and Researcher at Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. She holds an International PhD in Audiovisual Communication, Advertising, and Public Relations from Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she received several awards for her academic excellence. She has held the Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral contract and is a member of the Ciberimaginario Research Group. She has been selected as a crew journalist for the Hypatia II analogue mission at the Mars Desert Research Station in 2025. She has received over 25 scholarships and 8 Awards for Excellence in Research and has completed residencies at prestigious European and Spanish universities.

jennifergarciacarrizo@gmail.com

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0264-1931

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=Ey0TgxIAAAAJ&hl=es

Manuel Gertrudix

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Professor of Digital Communication and Multimedia at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, coordinator of the Ciberimaginario research group and co-editor of Icono14. Specialising in communication and digital education, he has led 12 research projects and participated in more than 25, with more than 150 publications. He was Vice-Rector for Quality, Ethics and Good Governance (2018-2021) and Academic Director of CIED (2013-2017) at the URJC. He has worked at the Ministry of Education and as a professor at various universities. He has completed research stays in the USA and Scotland and teaching stays in Argentina, Colombia and Brazil. He is the academic director of the Master's programme in Investigative Journalism, New Narratives, Data, Fact-Checking and Transparency at the URJC-El Confidencial.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5869-3116

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=A4gHKA4AAAAJ&hl=es

Appendix A - Tables

Table 3. Example quotes related to what information should be provided according to patients, healthcare workers, and media workers.

|

Variable and themes |

Example quotes |

|

1. What. What to inform |

|

|

1.1. The research that is being conducted on Long COVID |

“I’d like to find information on what is being researched and that money is being invested in this new illness” Patient 2. “Every week we have someone in charge of reading the scientific journals, what has been published, and depending on what we find we then publish information on the most relevant findings” Media 3. |

|

1.2. Workplace contact details for healthcare workers specialised in Long COVID |

“I’d like to find professionals who deal with the topic; specialist Long COVID doctors” Patient 14. |

|

1.3. The symptoms and treatments to cure or ease the effects of Long COVID |

“I’d like to know why this is happening to us and if there is any solution or solutions, whether there are any treatments” Patient 19. “Most published information is on COVID. But we are reporting everything from institutional information to other information that isn’t being covered too much by the Ministry of Health. In that regard, I think that for months medical bodies have been most actively and best highlighting it when it comes to warning about people that are getting Long COVID” Media 8. |

|

1.4. The existence of Long COVID as an illness and its institutional and healthcare authority recognition |

“There is generally a big lack of understanding, which is down to the lack of information, both from doctors, the media, and, therefore, from society. People can’t make sense of it. You’re constantly having to explain what’s happening to you and see people’s puzzled reactions because they really don’t know that this illness can trigger this condition. Things that don’t have a name don’t exist. And when they’re given a name, the truth must be told about what’s happening. There are thousands of us suffering from this problem and not just in Spain, but all over the world” Patient 37. “I don’t see much empathy from doctors. Honestly, you go to an appointment and they don’t even let you explain and they just tell you “well, that’s what you all say”. I mean, sorry, I don’t take a script with me to an appointment; if there’s a number of us with the same symptoms, I don’t think we’re making it up. We don’t like being ill or unfit to go about our daily lives” Patient 40. “I honestly think there is very little information on Long COVID and there should be much more information provided about it. I really think it’s because it doesn’t sell and there’s not much interest from the media. The population should be informed that if the symptoms or if a specific symptom persists over time and doesn’t go away, they should first contact their family doctor to tell them about these persistent problems so they can get the right treatment” Healthcare worker 8. |

|

1.5. The social, emotional, work consequences Long COVID has on the lives of those affected. |

“I would like more information in society... for it to be said on TV that there are so many unwell, in the thousands, in the hundreds, and these are the problems they have” Patient 3. “Apart from the physical effects, information should be given on waiting times and the time you are not protected” Patient 7. “It’s really important to try to raise awareness of COVID units and all these problems that people aren’t aware of... even social and economic problems, medical tribunals, being unable to work. We’re not reading about any of this in the media” Healthcare worker 2. “I think it’s essential to give an overview of how patients are dealing with it, how they feel, what’s happening to them” Healthcare worker 7. |

|

1.6. The presence of misinformation on digital platform, such as social media |

With COVID we’ve realised that apart from debunking the fake news and disinformation we find on social media, we also have to educate, and spread certain content. I mean, not just reacting to the disinformation we find, but rather play differently, informing the public about the real state of affairs of certain issues linked, in this case, to COVID in long-term effects” Media 9. |

|

1.7. Information on Long COVID linked to accounts from patient associations and/or healthcare workers and scientific societies. |

“We got a lot of accounts, especially in early 2020 and early 2021, from people who were giving their account both on effects and the persistent nature of them” Media 6. “We get some bits of information from professional associations, linked to doctors’ and nurses’ unions, who have caught it in the course of their work and now have Long COVID” Media 8. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 4. Example quotes related to when information should be provided according to patients, healthcare workers, and media workers.

|

Variable, themes, and sub-themes |

Example quotes |

|

2. When. When to inform |

|

|

2.1. In the setting / at the time of day that causes people affected by Long COVID to search for information |

“I can’t tell you a specific time of the day, but it’s when I’m feeling somewhat better” Patient 11. “When there are days I’m not well is when I most search for information because I’m keen to get over this” Patient 2. |

|

2.2. Frequency of publication of information |

|

|

2.2.1. Continuously |

“Information should be given continuously, yet logically and carefully. There are a vast number of people in this situation and it makes them feel they haven’t been abandoned. That is, that we're working on it, we’re still alert to all this problem, and that when sound studies are published, that’s when changes are made or consultations or recommendations are drawn up” Healthcare worker 2. “People are really busy with everything. You can’t always be checking the latest news. But, if you keep on coming across it, you’re eventually going to read it. I think it may be interesting to do it continuously”. Healthcare worker 2 |

|

2.3. In specific settings |

|

|

2.3.1. Long COVID Day |

“The idea of days for illnesses is really interesting, it seems silly but it’s not. Long COVID Day would be cool because it’s a way to remind everyone about a condition without going on about Long COVID every day” Healthcare worker 5. “There isn’t a Long COVID day. As soon as a Long COVID day does appear, I can tell you that’s when it will be done. I think it’s in a very early, very fledgling stage. So, information is published based on the studies that come out, I mean, studies in American journals, in scientific journals” Media 7. |

|

2.3.2. Results of interest |

“We’re going to keep on providing information as they studies move forward, when a new study appears and it is important, meaningful, people are given that new information” Healthcare worker 10. “When there is a solid study on the cause or some link between Long COVID and another type of illness or infection, we do prioritise that more. For example, studies on symptoms or studies on the prevalence of Long COVID. They are published as you get them, depending on the news interest of the information. If a new study appears on any issue that we think is interesting, we usually publish it while it’s still relevant” Media 5. |

|

2.3.3. Misinformation and/or disinformation |

“Our publishing criteria is based on whether we see significant concentrations of disinformation on those issues specifically, we take action and try to produce articles to be shared” Media 9. |

|

2.3.4. Concern in society |

“When we see that concern over this topic is growing, we set out in-depth reports on it” Media 12. |

|

2.4. Importance of Primary Health Care in referring to Post-COVID Units |

“Patients don’t contact us [the Post-COVID units] because they don’t know we exist, we haven’t been publicised due to a fear of overwhelming the system. I think that Primary Health Care is critical in that regard” Healthcare worker 2. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 5. Example quotes related to where information should be provided according to patients, healthcare workers, and media workers.

|

Variable, themes, and sub-themes |

Example quotes |

|

3. Where. Where to inform |

|

|

3.1. In primary care health centres and specialist centres |

“I’d like my family doctors or specialists to give me the information. I think they are the ones who should give me information about what’s happening to me and why it’s happening to me. But it hasn’t reached me” Patient 1. “What I’d like is not to have to search for information... if there was someone, a unit, someone who, when you went and told them what was happening to you, knew what you were talking to them about. Basically, I wouldn’t like to have to search for information. I’d like the doctors to give it to me” Patient 37. “I think firstly that healthcare workers are the ones who should inform the patient. The media is a good support but doctors must provide the information” Healthcare worker 6. |

|

3.2. An institutional platform that unifies all existing information |

“It’d be good if there was a page that summarised it all, with all the information on Long COVID so that we don’t go crazy. Especially so as to not read information we shouldn’t read. Because I think that, like everything in health or medicine, there are a lot of things that you don’t understand because you’re not a professional, so you may read it wrong or misinterpret it” Patient 4. “What I’m missing is some site where all the information is centralised. Because the problem now is that the centralisation of information is a bit chaotic. I think it’d be really interesting to have a website, an online platform where all the information form research, from studies, from everything that comes out was centralised and everyone could go there. Of course, it is on social media and the like, but it’s all abstract, it’s not organised. There is a lot of information that isn’t verified either. That is to say, I think in the end if you set up a website or a shared site where you can find all the information on Long COVID, it would be really convenient for everyone” Patient 20. “Imagine an official page on COVID from whatever Ministry where there is a page with a significant tab on Long COVID where patients can find out what units and which healthcare workers to go to clear up their problem. That’s basic information, I’m not talking about clinical trials” Healthcare worker 4. “A single, centralised source is needed so that the population can slowly find out, not just about Long COVID but about practically everything, that that source is the source to be trusted that is verified, that has lots of scientists behind it, and that, therefore, that’s where I, a member of the public, can go to also find information about Long COVID” Healthcare worker 10. |

|

3.3. The media as a way to raise awareness of Long COVID |

“The media should work to educate people about the illness, which is what is lacking right now. A good awareness-raising programme for society and scientific societies is needed. But, anyway, that’s not being done at the moment” Patient 5. “I think it is essential that institutions inform the public through the media about what is happening” Patient 12. “Both healthcare workers and patients send us press releases and tell us that we should raise awareness of Long COVID” Media 5. “Long COVID is problematic, it has so many associated symptoms that it is hard to know what it is; also, not enough information is available about the topic and it is difficult for us in the media to raise awareness of it without relevant findings or without further research into it; further research is needed” Media 10. |

|

3.3.1. Using both general and specialist media to segment the population and inform all groups. |

“If I had to increase awareness of a situation, I would possibly use everything, specialist media and also non-specialist media. I would call upon everyone. I don’t think we should limit communication to specialist media because we leave out the general population. There has to be a combination of everything. We have to target professionals and also the general public” Healthcare worker 1. “Using the media depends on the age range. (…) If you want to give effective information on Long COVID to people aged 18 to 25, use social media. If you want to talk to people aged 80, use a medical practitioner or healthcare worker. If you have a range of 30 to 50 or 60, use the radio or television” Healthcare worker 4. |

|

3.3.2. Distrust linked to the media |

“I don’t believe the media at all. The information they provide is totally biased and manipulated by the institutions” Patient 12. “I don’t trust the media that much. What normally comes out is very superficial; it doesn’t seem very reliable” Patient 26. |

|

3.3.3. Alarmism in the media |

“The media is really sensationalist, but they don’t get to the heart of it, of the mountains of information you need. Its point of view isn’t the illness but rather to cause alarm” Healthcare worker 3. “The media covers the type of information that sells and that gives them good headlines. So, the information that people should get from the media doesn’t match the information they have got” Healthcare worker 8. “Some media outlets have covered this topic in quite an alarmist way. (…) Some sites have covered it in an alarmist way whilst it would be interesting to cover it in quite a cautious and neutral way” Media 11. |

|

3.3.4. Lack of information |

“The problem is patients don’t have information. People go to their appointments and burst into tears. They don’t have good information and it’s also not that reliable” Healthcare worker 2. “My assessment of the information is zilch. Crap, shit. Whenever we finally have a lot of information on Long COVID, we’ll worry then about whether there is disinformation. The problem is that there isn’t even any fake news” Healthcare worker 4. “Our publishing criteria for this type of issue for exposure is whether we see significant concentrations of disinformation on those issues specifically” Media 9. “We “only” publish on Long COVID when we see something very worrying. We pick up the story and corroborate it, we confirm whether it’s true or not” Media 13. |

|

3.3.5. Agenda Setting |

“Patient associations are a particular pest, to put it like that. When they find you and see that you were receptive once, they’ll bombard you every day with everything that they're doing. That’s very good, it’s great they do that and it’s also their role. Part of their role is to support and assist those affected, but part of their role is to put the issue in the spotlight and make sure society understands their problem. And to do that they need the media” Media 2. “It’s been two years of the same story, so that plays against people who want to raise awareness of their cause and their problems... because I think the media is going to look elsewhere because what they’re looking for is clicks or revenue. We may get lucky if somebody famous or a politician gets Long COVID... maybe that’s how the issue will make a comeback and those affected will be “lucky”... But if not, they’re screwed, nobody is going to pay them any damn attention” Media 3. |

|

3.4. Using internet platforms |

|

|

3.4.1. Social media |

“We are pretty active on social media, we exchange information with others suffering from it” Patient 12. “Honestly, if it weren’t for Twitter, I’d be dead now. I’m that sure. For me, various international doctors and scientists that I follow on Twitter and are accessible on social media are key” Patient 16. “All the media has Twitter, Facebook,...they're now starting to get Instagram, YouTube channels. So, all channels are used because when you have a story what you want to do is get it out there” Media 2. |

|

3.4.2. Scientific platforms |

“I look for information online, on social media, and in specialist science pages, scientific publications, and I follow different scientists and doctors” Patient 16. “Searching on Google Scholar is critical for me; it gives me more reliable information than Google” Patient 28. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 6. Example quotes related to who should provide information about Long COVID according to patients, healthcare workers, and media workers.

|

Variable, themes, and sub-themes |

Example quotes |

|

4. Who. Who should inform |

|

|

4.1. Healthcare associations: primary health care doctors, specialist doctors, hospitals.

|

“I’d prefer institutions, my doctor, specialists to give information, because support groups, associations aren’t going to cure you. (…) They are useful in making you feel supported; in making you feel that there are other people going through the same thing as you, and that helps mentally; but the information should come from doctors, healthcare workers, and it should be official” Patient 17. “Faced with the lack of information, I ask a colleague who is also a nurse friend” Patient 15. “There are different medical associations, such as the Nursing Trade Union, which provides valuable information” Media 8. “A key source of information is doctors who are specialists in this matter or family doctors because they are the ones who deal with practically most Long COVID cases. Specialists in infectious diseases also provide interesting information” Media 11. |

|

4.2. Scientific bodies and organisations: universities, researchers, journals. |

“The sources of information should be the health authorities. Ministry of such and such, Autonomous Communities. But their ability to communicate accurate information over the pandemic has not been the best, far from it. That’s why we have to search for information more tied to specialists and scientific societies so that it is more suitable and accurate” Healthcare worker 8. |

|

4.3. Official Government sources |

“Information is always gathered from well-known and official sources, these are organisations, bodies, authorities who are recognised, have a track record... from the Ministry of Health to the Departments of Health in each Autonomous Community” Media 8. |

|

4.4. Patient associations |

“Firstly, the main source of information for those affected are the groups of those affected: associations and networks” Patient 5. “For me, accurate and reliable information comes from the association. They verify it and I trust them” Patient 22. “The patient associations must be considered a fundamental part of the structure of the health system, they are the ones who take in everything the health system can offer and it’s good to know what view they have. It is important to know what their view is and adapt the messaging to patient” Healthcare worker 1. “The ones that interest me and are the most important are the Patient Associations because they are the ones that are having a rough time of it and people ignore them, they are key” Healthcare worker 4. “There are starting to be a lot or at least several patient associations in Spain, aren’t there? I think this should be unified a bit. They are essential in the flow of information but they have to be coordinated” Healthcare worker 6. “Patient associations are very important. And they aren’t given the leading role they deserve given their ability to connect with a lot of people. They have to be included at all times, in any issue that affects patient health” Healthcare worker 8. “In health information, the most important actors are, on the one hand, the doctors and researchers. For the last ten years the associations have been key (...). Science is what assures you that you’re not talking nonsense. The person, the patient, and the person affected are what adds freshness and a human touch to those pieces of information which I know are very important. In that regard, the patient association are key” Media 2. “A main source is those affected, who are increasingly better organised and there are a lot of them, and therefore are the main source for the media” Media 3. “In the media, we speak to associations, we get their reports, we read them carefully. The experience of patients is really important. I mean that normally a patient who has an illness of this type, which is not widespread, is an expert patient, as they can give loads of useful information” Media 13. |

|

4.5. Specialist healthcare communicators |

“When providing information about COVID in the media there are mainly two profiles: there are journalists who have specialised over time in covering these stories and then there are external collaborators who are microbiologists, doctors, healthcare workers, and so on” Media 11. |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 7. Example quotes related to how information about Long COVID should be given according to patients, healthcare workers, and media workers.

|

Variable, themes, and sub-themes |

Example quotes |

|

5. How. How to inform |

|

|

5.1. Using a multidisciplinary, unified approach

|

“Applying joint pressure is critical; I think everything works better that way and all the research that is done on the internet should be published together, all the results should be brought together and everyone should be able to view them. I feel that everyone is fighting their own battle for their slice of glory, so in the end, these are very good studies but the only people to find out are those that have taken part in the study and the few people around them. In that regard, it is important to join forces and have the information in one place so that all studies work together” Patient 20. “The main problem is that there are a lot of very scattered studies and there is no centralisation in that area. And the working groups are, more accurately, independent professionals; everyone working in their field and the information is barely shared. Patient 30. “The key is for us to be able to be and use a coherent, solid, and understandable discourse for all the general public. (…) I think the key issue is being coherent, solid, and understandable” Healthcare worker 1. “Using a single set of criteria is very important and especially unifying treatments, recommendations, and avoiding, above all, that journey from one specialist to another and one doctor to another that we are witnessing. Bringing a lot of information together in one appointment is something patients appreciate a lot. (…) A multidisciplinary approach is key. When a patient comes to a unit and knows that the whole set of problems they have will be assessed, they feel confident. They feel they have the confidence to raise a lot of topics. But if they go to a five-minute appointment or are maybe bouncing around for a year and a half, it is impossible for them to feel they are being heard. In that regard, the problem is that there are many closed teams, and there is an attempt to monopolise the patient in different specialities. A respiratory medicine doctor talks about respiratory problems, thrombi, pulmonary issues, and so on. When you speak to an internal medicine doctor they speak about their field, but, in the end, there is no overall assessment of the patient” Healthcare worker 2. “These are patients that require a multidisciplinary response, I mean, they should be seen by Long COVID units, where there are multiple specialists because the symptoms that can be observed in their cases can vary greatly” Healthcare worker 6. |